The Heights was farms until the early nineteenth century, and the Dutch and British owners used slave labor there, as they did throughout Kings County. This is indicated by the fact that of the county’s population of 4,500 in the first U.S. census of 1790, one-third, or 1,500, were slaves. Bondage ended in Brooklyn in 1825, two years ahead of the date prescribed by New York’s Gradual Abolition Law of 1799, as amended. Very quickly, Brooklyn Heights and the surrounding area, which was then residential and would later become Downtown, exploded as a hotbed of abolition.

Slavery in Kings County was especially peculiar as the Dutch managed it. It was recognized that it was a money-based institution, but because there were only relatively small farms in the area rather than plantations, there were some humane features to this brutal practice. Bondsmen were allowed days off, could have their own side businesses, and could seek new masters if they disliked their owners, as is recognized by the black Historian Craig Wilder. The British were more callous in their attitudes towards bondsmen. They could not gamble, have more than twelve people at a funeral (probably for fear that such meetings could be used to organize slave revolts), and if found out at night were to be taken to jail to be whipped. As abolitionist feelings rose after the 1783 British evacuation of New York, public auction sales were ended in Kings County in 1790.

We know there were slaves in the Heights since a former Hessian soldier, John Valentine Swertcope, who lived there, allowed his slave Peggy to sell hot corn and pears with molasses on Fulton Street around 1800. In addition, the list below shows that Cornell and Hicks family members freed slaves, and these names are not known outside the Heights.

The New York Manumission Society, led by Alexander Hamilton (who had seen bondage in its worst form in the sugarcane fields of Nevis in the Caribbean where he grew up) and future Supreme Court justice John Jay, encouraged owners to free slaves and lobbied for abolition. In 1799 the State passed a law for its gradual abolition, which specifically authorized manumission (the freeing of slaves “by hand”), and required it end by 1827 when young people born that year would end the term of service the law prescribed they owed their owners.

The 1864 Manual for the City of Brooklyn lists manumissions (freed slaves) in all of Kings County after 1800. The first, however, was Caesar Foster, freed in 1797 under a 1788 law that allowed, but did not require it. During 1820, Anna Vanderbilt freed Margaret, aged sixteen years. Agnes Rappelyea let thirty-year old Anthony go in 1821, as did Leffert Lefferts with Henry, aged thirty-three. Adriance Van Brunt freed Sude, a thirty-five year old woman, and Jack, forty-four. Jeremiah Remsen freed thirty-one year old Nancy in 1820, and Selah Woodhull let Fanny, aged twenty-eight, go that year. So did Polhemuses, Hickses, Berrys, Duffields, Cornells, Freekes, Cowenhovens (often Anglicized as Conover), Strongs, Luqueers, Johnsons, Bergens and Birdsalls. While there were Remsens all over Kings County (there is a Remsen Avenue in Flatlands), the woman named Nancy freed by Jeremiah Remsen may have lived on the Heights.

However, all was not positive in manumission. It is clear that people who were legally free were being held in bondage, and that slaves were being purchased for the specific purpose of selling them south for a profit. Craig Wilder, now professor of History at M.I.T., reported in A Covenant with Color, the only book about slavery and black history in Brooklyn that:

In 1800 the New York Manumission Society charged that Captain Gilford of Flatbush was holding a free black woman from Nova Scotia in bondage. Peter Van Roden of Brooklyn bought Peggy Hull and sold her out of state before she could become free. Justice William Livingston of Kings County asked the Manumission Society to intervene on behalf of Harry, a servant who had been promised his freedom and fifty dollars in his owner’s will. John Lott, whose family bound twenty-six Africans on their Flatlands farms in 1790, seized Harry and his purse. The executors of the estate of Eleanor Simmons listed Margaret Ansley as a runaway, although Peter Courtelyou of Brooklyn witnessed her emancipation. (In 1790 the Courtelyous of Brooklyn and New Utrecht claimed thirty-two Africans.) A 24-year-old black woman was “sold for life” at auction in the Old Ferry Market. Administrator William Arnold did not display the bondswoman at the market, but made her available for private inspection in the preceding days, because public auctions were considered distasteful. Jacobus Van Nyun of New Utrecht illegally removed Lydia Hill to New Jersey where she remained enslaved. A store on the Williamsburg [Bushwick] border sold a 15-year-old black boy, “strong and in good health.” A 10-year-old black girl from Brooklyn was bound out until she was 25, a 15-year term of service offered even though slavery was to end in eight years. By 1820, when bondage was in marked decline almost everywhere else in the state, half of the African Americans in Kings County remained enslaved.

As early as 1800 the Standing Committee of the New York Manumission Society was decrying the “very general” practice of cheating the manumission law by transporting “Negroes from this to the Southern states… from whence they are reshipped to the West Indies.” The city also kept an open door for slave smugglers. “Any day of the week, slaves could be discovered stowed in the holds on board ships docked in New York harbor. They were brought from Africa, the West Indies, South America, and the American South, bound for reshipment to Southern plantations,” notes Anthony Gronowicz in his history of pre-Civil War Manhattan politics.

In 1819, a year after the founding of Brooklyn’s first independent black church, fugitive Africans seemed to be overtaking the county. Sam Johnson, an enslaved 10-year-old mulatto, liberated himself to the dismay of Cornelius Van Cotts of Bushwick, and a bondsman named Charles loosened himself from the Wallabout estate of Jacobus Lott. Lott forbade all from “harboring or employing said runaway under penalty of the law.” Johannes Stoothoff of Flatlands was particularly cross when his bilingual servant Dan, age 22, absconded. What most bothered Stoothoff was that Dan had permission to take leave for one day to look for a new master. Dan did exactly that when he decided to own himself but the arrangement was not to Stoothoff’s liking. Similarly, 38-year-old Yaff abandoned the Flatbush farm of Levi Hart on which he was enslaved. John Hegeman of Flatbush suffered the loss of two bondspeople, “a negro wench, named BET, and her boy, named Sam, about nine years old.” The 28-year-old mother took with her “a considerable quantity of clothing, and other articles.” Abraham Selover of Bedford was so vexed when his 25-year-old bondsman Peet escaped that he asked that hunters return him “or confine him in some jail” Garrit Vanderveer of Flatbush had his Bet, 28, flee (he warned his neighbors not to trust her), while 17-year-old Millane fled Brooklyn’s Losee Van Nostrand.

A suggested solution to slavery was the colonization of Africa by American blacks. Liberia, with its capital at Monrovia, named for President James Monroe, is the product of this effort. This scheme, although developed by whites who could not imagine a multi-racial society, engendered significant support over the years, most notably in the “Back of Africa” movement in the 1920s and ’30s of Marcus Garvey, who is seen as a prophet by Jamaican Rastafarians.

The New York State Abolition law provided that the counties should help maintain former slaves who were unable to earn a living. This was done via alms houses whose administrators were called Overseers of the Poor. David Ruggles, an early black abolitionist, reported in 1838 that Brooklyn overseer Lance Van Nostrand had illegally incarcerated a freeborn woman and her two children with the intention of selling them into southern slavery.

Throughout one will notice the prominence of wealthy businessmen in the abolitionist movement. This was the product of their belief in “free labor”, a founding principle of the Republican Party, which held that business needed workers with the flexibility to move from job to job and place to place as economic conditions required. While slavery was inconsistent with this concept, “free labor” would later have anti-labor implications.

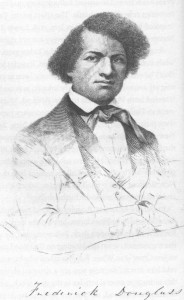

Adrien Van Sinderen was the first president of the Brooklyn Savings Bank. He moved from 58 Willow Street to No. 70 , his new house, around 1839 (the caption above seems to be incorrect). He helped found a Brooklyn branch of the American Colonization Society in 1830, and gave freedom seeker Reverend James W.C. Pennington, a runaway originally from Maryland, by way of  Pennsylvania, a job as a coachman, probably in 1829. Clearly, Van Sinderen opposed slavery, but could not imagine a multi-racial society. He died before 1850. Pennington is probably best-known for performing the wedding of Frederick Douglass to Anna Murray at the home of David Ruggles.

Pennsylvania, a job as a coachman, probably in 1829. Clearly, Van Sinderen opposed slavery, but could not imagine a multi-racial society. He died before 1850. Pennington is probably best-known for performing the wedding of Frederick Douglass to Anna Murray at the home of David Ruggles.

Here is Craig Wilder on Pennington:

The most prominent African to escape to Brooklyn was James W. C. Pennington, born James Pembroke in 1807. In 1829, he ran away from the eastern shore of Maryland. A long and dangerous flight brought Pennington to the North where he “went to New York, and in a short time found employment on Long Island, near the city [in Brooklyn].” He found his life’s work while attending classes in the black community’s evening schools:At length, finding that the misery, ignorance, and wretchedness of the free coloured people was by whites tortured into an argument for slavery; finding myself now among the free people of colour in New York, where slavery was so recently abolished; and finding much to do for their elevation, I resolved to give my strength in that direction.” In 1830 the Brooklyn Temperance Association was organized to reduce drunkenness and disorder. Benjamin Croger was president, Pennington was secretary, and George Hogarth, a minister and a teacher at the area African school, was a manager. A year later Pennington helped construct the public statement of a convention of Kings County’s black residents in opposition to the local ACS’s schemes to relocate free colored people to Africa and Haiti. The parents of black children on Long Island felt Pennington’s presence through his constant proselytizing to get them to send their youngsters to school. He served as instructor at a new school for Africans in Newtown, Long Island. The fugitive turned teacher attended classes at Yale Divinity School, although its officials would not formally allow him to enroll, and in 1837 was licensed as a preacher in Brooklyn. In the following years Pennington received the degree doctor of divinity from the University of Heidelberg, became a major antislavery spokesman in the United States and Europe, and was installed as pastor of an African church in Manhattan. In 1852, in the concluding remarks to her Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Harriet Beecher Stowe added Pennington to a list of “individuals [who] have thus bravely succeeded in conquering for themselves comparative wealth and social position, in the face of every disadvantage and discouragement.

Beginning in 1831 J. W. C. Pennington represented Brooklyn at the first Conventions in Philadelphia and New York. “A public meeting was held on the 27th of March [1832], when Mr. James Pennington was duly elected the delegate to the Convention from this village,” announced “A Colored Freeman” from Brooklyn.

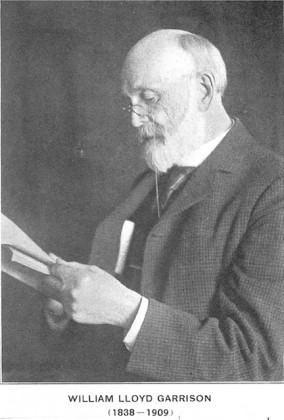

Today religious reformers are conservatives, but in the nineteenth century they were liberals. (The major exception to this within living memory is the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and sixties.) It is not generally known that the reform movements of the nineteenth century were a product of intense religious feelings. It is therefore not an accident that Rev. Henry Ward Beecher is the best-known New York City abolitionist–among both whites and blacks it was principally a religious movement. Its intensity was, to a great extent, a product of the Second Great Awakening of the 1820s through ‘40s which generally revived religious feeling in the U.S., and therefore ended the Age of Enlightenment. Among both white and black foes of slavery, most were deeply religious or religious leaders. Indeed, the only major leader who was not was William Lloyd Garrison. Besides abolitionism, the Awakening also led to the Women’s Suffrage Movement, strengthened temperance, and led to the founding of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. All of this took place in western New York State, near the Erie Canal, which was rapidly modernizing life there and generating a religious reaction. The Civil War may be considered a religious crusade as indicated by the lyrics to the Battle Hymn of the Republic, whose composer, Julia Ward Howe, was also an early feminist.

Today religious reformers are conservatives, but in the nineteenth century they were liberals. (The major exception to this within living memory is the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and sixties.) It is not generally known that the reform movements of the nineteenth century were a product of intense religious feelings. It is therefore not an accident that Rev. Henry Ward Beecher is the best-known New York City abolitionist–among both whites and blacks it was principally a religious movement. Its intensity was, to a great extent, a product of the Second Great Awakening of the 1820s through ‘40s which generally revived religious feeling in the U.S., and therefore ended the Age of Enlightenment. Among both white and black foes of slavery, most were deeply religious or religious leaders. Indeed, the only major leader who was not was William Lloyd Garrison. Besides abolitionism, the Awakening also led to the Women’s Suffrage Movement, strengthened temperance, and led to the founding of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. All of this took place in western New York State, near the Erie Canal, which was rapidly modernizing life there and generating a religious reaction. The Civil War may be considered a religious crusade as indicated by the lyrics to the Battle Hymn of the Republic, whose composer, Julia Ward Howe, was also an early feminist.

Robert Furman is working on a history of Brooklyn Heights called “Brooklyn Heights: The Rise, Fall and Rise of America’s First Suburb,” to be published later this year.