Sandy Ikeda is a professor of economics at SUNY Purchase, and a resident of Brooklyn Heights. He’s also a very personable and bright guy, as your correspondent can attest, having gone on two Jane’s Walks through the Heights that he led, one several years ago and one this April. On each occasion he showed extensive knowledge of the neighborhood, including information that I, a resident of thirty years, didn’t know.

For example, I learned that the townhouse on Clinton Street in the photo above served, in the time just after the conclusion of World War II, as a halfway house for Japanese-Americans who had been interned in camps during the war.

For example, I learned that the townhouse on Clinton Street in the photo above served, in the time just after the conclusion of World War II, as a halfway house for Japanese-Americans who had been interned in camps during the war.

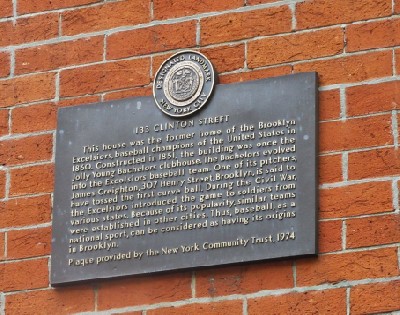

Then there’s this plaque on the townhouse at the corner of Clinton and Livingston, that identifies it as having been the clubhouse of the Brooklyn Excelsiors, baseball champions in 1850, and one of whose pitchers may have invented the curve ball. The Excelsiors were lineal ancestors of the Brooklyn Dodgers, my first love in baseball, even though I lived nowhere near Brooklyn at the time.

Then there’s this plaque on the townhouse at the corner of Clinton and Livingston, that identifies it as having been the clubhouse of the Brooklyn Excelsiors, baseball champions in 1850, and one of whose pitchers may have invented the curve ball. The Excelsiors were lineal ancestors of the Brooklyn Dodgers, my first love in baseball, even though I lived nowhere near Brooklyn at the time.

Despite his knowledge of, and obvious love for, Brooklyn Heights, Sandy has argued here that the designation of Brooklyn Heights as a landmarked historic district was a mistake. He says he and others have benefited from it; they “enjoy the quiet and charm of a place nearly frozen in time – we basically live in a museum with restaurants.” The problem, he says, is that the restrictions imposed by landmarking have constrained how owners may use or dispose of their property and, for a more far-reaching effect, have limited the supply of housing over the whole local market, making it less affordable for all.

These were “Jane’s Walks,” and Sandy is an admirer of Jane Jacobs, whose The Death and Life of Great American Cities and The Economy of Cities examined the question, “What makes cities work?” She championed the idea of the “neighborhood,” an area incorporating a mix of uses: residential, commercial, and public (schools, libraries, police and fire, parks) and a mix of old and new buildings housing people of diverse economic means. She opposed attempts to impose order or rationality through “urban renewal” schemes that were popular in the 1950s and ’60s. Neighborhoods, she thought, should be allowed to develop organically.

Jacobs also fought against the construction of highways through urban neighborhoods, which destroyed large parts of them and created divisions where none had existed before. Sandy noted with approval the efforts by Brooklyn Heights residents to keep Robert Moses from routing the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway through Brooklyn Heights, an effort that caused Moses to re-route the highway to the edge of the bluff atop which the Heights sits, and to create the Promenade above it. Like Jacobs, Sandy saw Moses’ original plan to route the highway through the Heights as a heavy handed government intrusion into a neighborhood; one that would alter its character for the worse.

How, then, did landmark designation, which was brought about by local residents (though no doubt some were opposed) violate Jacobs’ principles? She believed neighborhoods should develop organically, but also (according to this brief bio) was “[a] firm believer in the importance of local residents having input on how their neighborhoods develop.” I didn’t put this question directly to Sandy during our Jane’s walk, but I think his answer would have been twofold: first, by tying their own hands with regard to the disposition of their properties, owners at the time of landmarking were also tying the hands of future generations of owners who had no voice in the matter; and second, that the wishes of the neighborhood’s residents in this respect were outweighed by the city’s need for greater density (which Jacobs also advocated) and the affordable housing this would make possible.

I haven’t found any indication that Jacobs took a position, pro or con, concerning the landmarking of Brooklyn Heights, which occurred a few years before she left New York for Toronto. I have learned, though, that Brooklyn Heights was her first home in New York City. She and her sister Betty lived on a block of Orange Street that, some time after they moved out, was demolished to make way for Moses’ Cadman Plaza housing development.

As Sandy and I walked along the Promenade, I asked him if, had Brooklyn Heights developed “organically,” we would be seeing a phalanx of high rises to our right instead of the backs of townhouses and their gardens. His first response was, “Yes,” but then he quickly added, “Well, you can’t really tell.” That’s true; real estate markets have their ups and downs, as do cities as preferred places to live. It’s also possible that the owners of townhouses along Columbia Heights might have made a pact not to sell to any developer. How enforceable that would be, and how long it could be effective, are relevant questions. It’s not unknown, though, for property owners to refuse a deal that would be lucrative in the short run in order to preserve a pleasant ambiance and the prospect of long term appreciation in value. This is just what happened when the owners at 75 Henry Street, part of the Cadman Plaza high rise complex, voted to say “no” to a developer’s offer that would have resulted in the construction of a new high rise on the location of the Pineapple Walk shops.

For better or worse, New York, and Brooklyn in particular, is now considered very desirable. My guess is that the Heights, without landmarking, would today have the phalanx facing the water and many, though not all (some still survive in Midtown East), stretches of attractive row houses (as in the photo above) demolished and replaced by tall buildings, casting many shadows over the neighborhood. The Columbia Heights phalanx would make the Promenade a less attractive place to visit. I think the Heights would still be largely a “residential monoculture,” as that seems, in economic terms, the “highest and best use” as determined by market demand. We’d still have restaurants, probably more of them, and perhaps more high end retail.

What Jane Jacobs may not have foreseen when she wrote her first two great books was that her beloved West Village would be overrun by, well, people like me: people who could afford $350 a month (in 1973) for a one bedroom in a gut rehabbed tenement; people with jobs in law firms (like me), ad agencies, or banks, but who harbored artistic pretensions and were looking for authenticity, instead of the sterility of the Upper East Side or, heaven forbid, the suburbs. This began a trend of gentrification that led to what my friend David Coles describes here. Much of the West Village, like the Heights, became a landmarked district. It also became devoid of what Jacobs praised: a mixture of uses and of people of differing economic circumstances.

The Heights went through a similar process of gentrification, well described with respect to Brooklyn generally by Suleiman Osman in his The Invention of Brownstone Brooklyn. The early gentrifiers were in the vanguard of those seeking designation of the Heights as a historic district. Today it is a much less economically diverse community than it was in the 1960s and before, and commercial rents have risen considerably, forcing out some locally beloved stores, the latest being Housing Works. I believe, though, that these changes would have happened with or without landmarking. Any new high rises built in the Heights, because of its proximity to water and its pre-existing charm. would have commanded very high rentals or asking prices. Their combined effect would have been to make the neighborhood less attractive, but not enough to make it affordable for those of moderate means.

Jane Jacobs may not have foreseen gentrification, nor the ability of private developers to disrupt neighborhoods by (sometimes surreptitiously) acquiring assemblages of land and purchasing air rights in order to put up massive structures. I asked Sandy if he believed that private, as well as government, entities could impose on neighborhoods in ways that frustrated Jacobs’ notion of organic development. He unhesitatingly replied, “Yes.”

The question is, was the landmarking of the Heights worth it on a cost versus benefit basis? I would say it was. To Sandy’s first objection, that it puts a burden on property owners in the district, I would say: should the burden become too great for a majority of them, they may petition the city to remove it. To the objection that it constrains the supply of available housing, I would say that the constraint, in the case of the Heights, is minor. My further answer would go to less economic than, dare I say, historic and romantic considerations. I think it’s important to save some neighborhoods, like the Heights and the West Village, as reminders, imperfect as they may be, of what the city once was like, and of the history that played out in them; not only, as in the case of the Heights, that Washington’s army camped here in August of 1776 and that he planned his troops’ escape from Long Island here, or that many great artists, writers, and political figures have made homes here, but also in the more impressionistic words of Truman Capote in his A House on the Heights:

These houses bespeak an age of able servants and solid fireside ease, invoke specters of bearded seafaring father and bonneted stay-at-home wives: devoted parents to great broods of future bankers and fashionable brides.

Landmarking couldn’t save residential or commercial diversity in the Heights or the West Village, but lack of landmarking wouldn’t have, either. Indeed, it would likely, in my opinion, have made things worse.

Photos: C. Scales for BHB.