As part of urban renewal, the Mechanics Bank Building on the northwest corner of Fulton and Montague Streets, which had housed the Brooklyn Dodgers’ front office, was razed in 1958. History was made in that building with the signing of Jackie Robinson by General Manager Branch Rickey in 1947. The bank itself had been absorbed by the Brooklyn Trust Company, part of a continuing trend toward bank consolidation and of their going national and now, international.

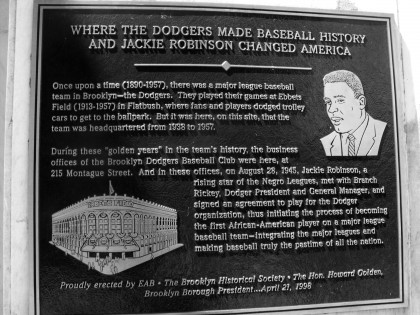

Strangely enough, in the era of high rises, this notable ten-story structure was replaced by a four-floor building whose first tenant was the Brooklyn Savings Bank and still bears the chiseled inscription “Founded 1827,” a poor souvenir of what had been Brooklyn’s second oldest bank, begun in the Apprentices’ Library. Below this is a 1998 plaque that tells the story of Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey integrating baseball.

The Dodgers held many of their annual dinners in the Hotel Bossert, including the one when they finally won the World Series in 1955. The Bossert wasn’t the Dodgers’ exclusive hotel for visiting players, many of whom stayed the Towers Hotel.

The major symbol of Brooklyn’s decline is the departure of the Dodgers for Los Angeles in 1958. The Brooklyn Trust Company, the team’s bank, is now the Chase branch at Montague and Clinton Streets. Their General Counsel, Walter O’Malley, although a civic leader (he was a vice president of the Brooklyn Club), and a major stockholder in the Long Island Railroad and Brooklyn Union Gas Company, came to own the Dodgers and move them. A proposal for a new stadium at Atlantic Terminal failed.

Walter O'Malley (l) with NY Giants owner Horace Stoneham hold model of proposed domed Brooklyn baseball stadium in 1957.

O’Malley demanded that the city build a new, larger stadium with adequate parking and deed it over to him, as L.A. had promised to do and eventually did. Robert Moses was uncooperative with using eminent domain to further private interests, and Mayor Robert F. Wagner felt the demands were extortionate and that if he had complied with them he would have been impeached! The city offered a new stadium in Flushing Meadow Park, which pleased neither Dodger fans nor O’Malley because it was in Queens, where the new National League New York Metropolitans would obtain a city-financed (but team owned) stadium in 1965.

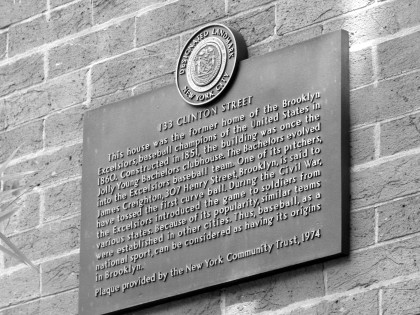

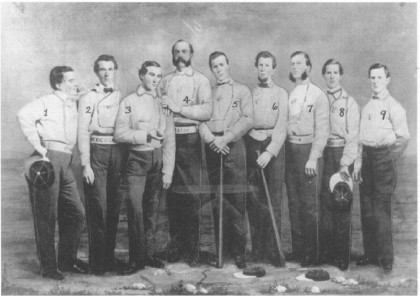

This and the Brooklyn Trust branch are not the only Heights sites crucial to baseball history. A plaque on 133 Clinton Street notes that it was the clubhouse of the Brooklyn Excelsiors, an amateur club who were U.S. champions in 1860 when the sport was in its infancy and known as the “New York game.” They began its professionalization. According to the plaque, they began as the “Jolly Young Bachelors” and then the “Bride-grooms,” names redolent of the old aristocracy indicated by the membership of young men with names such as Pearsall and Polhemus. They eventually became the Dodgers, and the building and organization of the Excelsior Club became a social club by 1874 which persisted into the 1930s.

BASEBALL. An Illustrated History by Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns reports that the Brooklyn Excelsiors played the Atlantics for the championship of the City of Brooklyn on August 20, 1860. The Atlantics were a working-class nine and went on to become the dominant team of the 1860s. The Brooklyn Niagaras fielded baseball’s first star, James Creighton, who is credited with inventing the legal fastball. He later moved to the Brooklyn Stars and then to the Excelsiors. He died in 1862 of a ruptured bladder after hitting a home run. Another Brooklynite, William Cummings, came up with the concept of the curveball at age fourteen and went on in 1867 to beat a Harvard College team with this innovative pitch while playing for the Excelsiors. Another Brooklyn player invented the bunt.

Robert Furman is working on a history of Brooklyn Heights called “Brooklyn Heights: The Rise, Fall and Rise of America’s First Suburb,” to be published later this year.