The Congregational Church of the Pilgrims and its founding pastor, Rev. Richard Salter Storrs, are probably the most underappreciated place and person in the Heights, because the church no longer exists. Plymouth was born out of Pilgrims, at Remsen and Henry Streets, whose members had left the First Presbyterian. The men who founded Plymouth felt that Pilgrims was too conservative.

The Congregational Church of the Pilgrims and its founding pastor, Rev. Richard Salter Storrs, are probably the most underappreciated place and person in the Heights, because the church no longer exists. Plymouth was born out of Pilgrims, at Remsen and Henry Streets, whose members had left the First Presbyterian. The men who founded Plymouth felt that Pilgrims was too conservative.

Pilgrims was designed by Richard Upjohn, who was also the architect of Grace Episcopal on Hicks Street and Grace Court in 1849, and of Manhattan’s Trinity Church, Pilgrims was the first Early Romanesque Revival building in the U.S., and served as a model for other evangelical Protestant denominations. It was expanded in 1869 with a High Victorian addition by Leopold Eidlitz, and this is one of his few surviving buildings, although he was a major figure in American design.

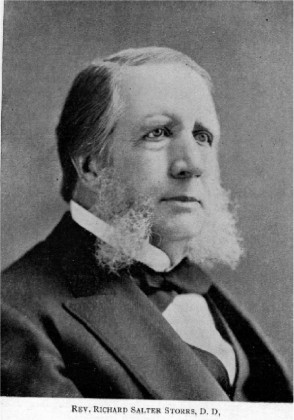

Its minister from its opening in 1846 until just before his death in 1900 was Richard Salter Storrs, in his time almost as famous as Beecher, indicated by the fact that he presided over the opening ceremonies for the Brooklyn Bridge, which was a Brooklyn sponsored project (hence the name). He lived at 34 Livingston Street when the church began, then at 80 Pierrepont Street (Figure 188) and later at 1 Pierrepont Street (demolished) where he died. The church owned a piece of Plymouth Rock, now housed at Plymouth Church.

The Church in 1904. Most noticeably, the spire has been removed because of damage in the Great Hurricane of 1938.

Storrs was also an active abolitionist and gave a speech after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850 that counseled the moral obligation of disobedience to the law; i.e., that Christians had an obligation to aid escapees but had to accept the consequences of punishment, while the fugitive had the right to resist kidnapping via his right to self-defense.

In a sermon titled “The Obligation of Man to Obey the Civil Law: Its Ground and its Extent, a Discourse Delivered December 12, 1850, on Occasion of the Public Thanksgiving in the Church of the Pilgrims, Brooklyn, N. Y. by Richard S. Storrs, Jr., Pastor of the Church,” he counseled all who heard that no one had an obligation to obey an unjust law, and in fact, were morally obligated to disobey it and to actively aid fugitive slaves.

A small but significant extract follows which recommends both civil disobedience and suggests the fugitive has the right to resist kidnappers by force! The sermon was so influential it was reprinted in book form.

Though its penalties were accumulated to tenfold greatness, they should not shut my doors against him [the fugitive slave]. You will not resist the law by force and violence. I will even advise the Man to flee it if he can, and not resist it, although it hurls him back upon his right of Self-Defence. But I will not obey it, unless by bearing its penalties. The man who does otherwise is in peril of his Soul. For Eternity is grander than crime and its scenes!

The participation of the Heights and Downtown in the abolitionist movement was so total that word got around to fugitive slaves that they could knock on the door of any church there and discover succor! According to a speech by Storrs in 1889 reported in the Brooklyn Eagle, in the early 1850s, such a man appeared at the threshold of the Reformed Church on Joralemon Street, an institution whose minister, Dr. Maurice Dwight, had previously said Storrs was “going to the dogs” for his abolitionism. Dwight was so moved by the specter of a human tragedy in the making, that he took the refugee to Storrs and asked how he could help.

The Brooklyn Eagle of April 23, 1889 covered Dr. Storrs’ speech at the Congregational Club at the Congregational Church of the Pilgrims:

Dr. Storrs related an incident about the Rev. Dr. Dwight, who early in the fifties was pastor of the First Reformed Church in Brooklyn, and was a warm friend of the speaker. He was of Southern birth. It happened that Dr. Storrs preached an earnest sermon denouncing the Fugitive Slave Law and declaring that he would never be bound by it nor would he obey it. Dr. Dwight expostulated with him as a friend and feared that Dr. Storrs had ruined his chance for usefulness in the community, but Dr. Storrs was flinty about it and did not repent. A week later, one stormy Saturday night, Dr. Dwight came to Dr. Storrs’ door in the pouring rain, with a man as black as the night, and explained that the poor fellow was a runaway and he wanted Dr. Storrs to tell him where he could take the man for safety. Dr. Storrs wanted to go himself and relieve Dr. Dwight, but the latter would not hear of it, nor would he permit Dr. Storrs to bear a part of the expense, bSut insisted on doing the whole work himself. So Dr. Storrs told Dr. Dwight where to take the man over in Nassau Street, where there was a depot on the underground line.

“As long as this more abstract question was concerned,” said Dr. Storrs, “he thought I was going to the dogs, but when the reality was presented to him, he went to the dogs faster than I did.” [Applause.]

Storrs offered to take the escapee to a “depot” of the Underground Railroad on Nassau Street (probably African Hall about which little is known), but Dwight insisted on doing this himself and bearing the expenses!

80 Pierrepont Street was the home of Rev. Richard Storrs. The stoop has been eliminated and a simplified pseudo-Federal entry has replaced it. The Behr house is at left.

The process by which neutrals became abolitionists is fascinating in itself. It often involved fleeting contacts with the peculiar institution rather than the presence of kidnappers operating on northern streets. The experience of Rev. Storrs is instructive. He spoke to the Congregational Club on how he became an abolitionist. His talk was covered by the Brooklyn Eagle on April 23, 1889. In it he contrasts and compares the history of his own involvement with that of Oliver Johnson, an abolitionist, Underground Railroad participant and editor of The Anti-Slavery Standard:

“My point of view,” continued Dr. Storrs “was not antagonistic to him (Oliver Johnson) but was different. It began later with me. It was about 1845 when I began to be active in affairs, and Mr. Johnson had already been twelve or fourteen years at work in the field. My personal position was such that it had an effect in modifying my view on the question. I was never an apologist for slavery, but I was never under the control of the ideas put

under the control of the ideas put forward by the men who circled around Mr. Garrison and the immediate group of friends who followed his lead. Through Mr. Wendell Phillips, with whom I was brought in frequent contact, I knew very much about what went on within the inner circles of the Abolitionists as to what they were doing and as to the ideas which dominated them, and learned also to appreciate the worth and character and earnestness of Mr. Garrison and those about him. But although very familiar with what they were doing I was not of them. In 1849, however, I was suddenly converted to an intense hostility to slavery by an incident which I shall never forget, either in this life or in the immortalities. I was coming home from Richmond, after a trip of some weeks through Virginia. I had seen no evidence of cruelty. I had come down by rail to Aquia Creek, there to take the boat for Washington. When the boat came in people poured off to take the train to Richmond.Behind them, under charge of a couple of men, came about twenty or thirty colored children, ranging in age from 8 or 10 years, up to, perhaps 16 or 18 years, they were well fed, healthy looking children, comfortably clad and at first I said, “Why, here comes a colored Sunday School.”

Behind the children came a colored woman, no darker of skin than many a brunette in the North, and great tears were rolling down her cheeks. A little child was clinging to her dress, in one hand she carried a bundle and with the other led along a sickly looking boy. Nearly every child had a little bundle. As the woman came off the boat she looked at me full in the face and I saw her grief and then it came to me like a flash what the scene meant. Those children had been picked up by the dealers around Washington and were being taken to Richmond, there to be scattered over the south from the auction marts in that city.

That woman was on her way to separation from her children. I was hastening home to the bedside of a sick child, and as I stood there I thought “Can anything make it right to sell wife and child? Could a whole book filled with make it right?” And I thought that I would be burned alive before I would consent to such a thing in my own case, and then I will be burned alive before I will excuse or palliate the system which makes such a thing possible. [Applause] I never felt after that that there was anything excessive in Wendell Phillips’ declaration, “Your national banner clings to the flagstaff covered with blood.”

As the old Protestant population continued to flee the Heights for Manhattan and the suburbs, Plymouth Church merged with the Church of the Pilgrims in 1935, and they combined at Plymouth on Orange Street. The Pilgrims building became Our Lady of Lebanon Maronite Rite Roman Catholic Cathedral in 1944 as a large population of Near Eastern Christian Arabs migrated to Brooklyn from lower West Street in Manhattan, where they had been displaced by the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel. Its pastor is the Most Rev. Gregory John Mansour. Besides serving as a religious home for the Near Eastern Christian community, the church also houses the Brooklyn Autism Center.

Medallions from the brass doors on the dining room of the French liner Normandie, which burned and capsized at its berth on the Hudson River in 1942, were purchased at auction by the church in 1945 and mounted on its new brass doors (which replaced the old wooden ones). The spires shown in the picture of Pilgrims were damaged in the Great Hurricane of 1938 and removed. New stained-glass windows by Marc Chagall replaced the original ones removed to Plymouth after the merger.

Robert Furman is working on a history of Brooklyn Heights called “Brooklyn Heights: The Rise, Fall and Rise of America’s First Suburb,” to be published later this year.