Daisy and I had already been quarreling for the 500 years we’d been together. She demanded the right to dig up carpets, nest in the dishwasher, pee where she pleased and, worst, draw human blood as though it was tap water. Several times a day I had to spray my quite elderly mother with Bitter Apple in order to keep Daisy from sinking her fangs into her legs and hands.

Daisy and I had already been quarreling for the 500 years we’d been together. She demanded the right to dig up carpets, nest in the dishwasher, pee where she pleased and, worst, draw human blood as though it was tap water. Several times a day I had to spray my quite elderly mother with Bitter Apple in order to keep Daisy from sinking her fangs into her legs and hands.

When my brother stuffed Daisy into the crate at the airport, he turned to me and said, “You know, you don’t have to keep this dog.” His words sealed my pact with the little pagan, although everyone on the plane had to listen to her barking in the hold for the Twin Cities – La Guardia leg of the trip.

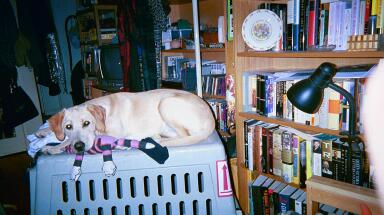

Daisy has hated crating ever since. When she was small, I could wrestle her in when I abandoned her for such frivolous exigencies as appearing on The Today Show. I kept the crate out for a long time in the hopes she would remember how much she liked it in her Montana infancy but at best she showed only contempt for it.

While my brothers kindly produced grandchildren for my parents, I am the child who has brought home the sole grand-Lab. I learned to walk in the midst of a litter of 15 Labrador puppies and my father relishes stories of hunting with the Pat and Sandy, Jet and Buff. Labradors are part of my family’s lore and if I showed up at Christmas without Daisy, my mother might refuse to let me in the house.

We’ve done a fair amount of flying. Daisy’s five now and shows a remarkable sensitivity for the nonagenarian pace and abilities of my parents’ life in an Arizona retirement city. She spends a lot of time getting belly rubs while sandwiched between them in bed and my father, ever one for canine discipline, feeds her at the table.

She’s still capable of tantrums for me. I have to muzzle her at her veterinarian’s, and we’ve worked out a system whereby I walk her to the scale, which she hates more than I do, and hand her off while I go straight out the back door. When I’m not there to play to, she gives up and submits. I’ve found that Western vets tend not to put her up on the table, which is enormously relieving to her, but we don’t have a veterinarian in Arizona who knows her history of hysteria.

After her first flight, her vet prescribed something wonderful. An hour after taking it, she can’t walk a straight line and her third eyelids roll around like a liver and oyster casserole. It’s against one Continental’s rules to tranquilize animals so at check-in, I lie about her drug usage, she balks enough to convince the handlers, and we’re on our separate ways to the same place.

We performed this routine when we flew out of Newark on December 18th. Unfortunately, while I had thought of everything I might need for myself, and more than enough to make a memorable Christmas for my parents, I forgot one thing: her travel pills.

This is her ninth airplane trip, I thought when I emptied my luggage and discovered the missing magic red bottle, she’s smart enough to know this is how we stay together. And I know Daisy’s greatest fear – beyond crates, Havaneses and other suspicious dogs and people, snowmen and abandoned inside-out umbrellas – is not being with me. We’ve been a team ever since my brother suggested I give her up.

I didn’t know what true fear could turn her into until our departure time was delayed two hours. We had sat together in the Pet Pack office and I read John LeCarré while she trembled, huddling close to me. Those shivers were the rats in the attic that preceded Regan’s spinning head. I was about to meet Captain Howdy.

BHB columnist Frances Kuffel has lived in the Heights for twenty years. Her dog walking clients include Augie, Barley, Boomer, Faith, Gus, Henry, Hero, Panda, Roger and Zeke. For more information, visit http//franceskuffel.net, http://caronthehill.blogspot.com, or http://www.flickr.com/photos/kuffelscrapbook. She is the author of Passing for Thin.