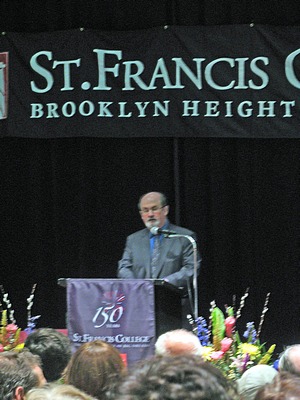

Award-winning novelist Sir Salman Rushdie delivered the eleventh annual Thomas J. Volpe lecture to a packed auditorium at St. Francis College this afternoon. His topic was “Public Events, Private Lives: Literature and Politics in the Modern World.”

Award-winning novelist Sir Salman Rushdie delivered the eleventh annual Thomas J. Volpe lecture to a packed auditorium at St. Francis College this afternoon. His topic was “Public Events, Private Lives: Literature and Politics in the Modern World.”

Rushdie began by noting that, in the nineteenth century, works of fiction often were the sole means by which people received news about events or conditions, even in their own countries. He cited Charles Dickens’ novels as exposing conditions among the poor in Britain, leading to legislation to ameliorate their plight. “The novelist who had the greatest impact on history”, he said, was Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin

and sister of Heights resident and Plymouth Church minister Henry Ward Beecher. Rushdie quoted Lincoln, on meeting Stowe: “So, you’re the little lady who started this big war.”

Do we need books to give us news today? Rushdie said we do. First, he noted the poor quality of the “news” most of us get through mass media, with its fixation on celebrities and the trivial. He said we can learn much about people and attitudes in parts of the world that our media do not or cannot cover by reading novels like The Kite Runner or memoirs like Reading Lolita in Tehran. Rushdie then said there is an inherent tension between politicians and writers, especially where the political regime is unpopular, as both wish to control what is represented as true. He quoted Milan Kundera as calling this “the struggle of memory against forgetting.” What those in power wish to be forgotten, the writer is tasked with keeping in memory. Rushdie gave two examples. One was the mass murder by the Pakistani Army, just before it withdrew from what is now Bangladesh, of many of that country’s writers and other intellectuals, who were buried in shallow graves near the capital city of Dhaka. This was an attempt to control who could tell the story of Bangladesh’s (formerly East Pakistan’s) struggle for independence. The second was Indira Gandhi’s refusal to leave office for several days following her party’s loss of an election, during which she had burned all of the papers documenting her government’s actions during a period of “emergency rule” in which she exercised dictatorial powers. Rushdie has tried to keep alive the memory of some of the things that happened during that period in his novel Midnight’s Children.

One salient difference between our time and the nineteenth and earlier centuries, Rushdie said, is the decrease in the space between the private and the public realms. For example, the novels of Jane Austen were written during the time that Britain was embroiled in the Napoleonic wars, but the wars do not intrude on the lives of the characters (except perhaps indirectly, through the increase in land values they occasioned) and are scarcely mentioned. Today, people’s private lives are increasingly affected profoundly by events in the public sphere, such as the current economic crisis and September 11, 2001. No longer, Rushdie said, can a writer accept without qualification the claim of the Greek philosopher Heracleitus that “character is destiny.”

Rushdie recalled a scene from Saul Bellow’s novel, The Dean’s December, in which the protagonist, a college dean from Chicago, is visiting his wife’s home in Romania when that country was still under Ceaucescu’s dictatorship. While standing by a window looking out over a bleak scene, the Dean hears a dog barking insistently in the distance. After the barking has persisted for some time, the Dean muses that the dog is protesting against the limitations imposed on its understanding by its dog-ness. “Open up the universe a little more” is what he understands is its message. The writer’s task, Rushdie said, is to try to open the universe a bit, but he warned that there are those who will push back because they want very much to keep the universe closed.

Rushdie, who grew up Muslim in India, was the subject of a fatwa calling for his death, issued by the Ayatollah Khomeni of Iran as a result of his novel The Satanic Verses, which was considered by some to be blasphemous. Of the Ayatollah, Rushdie noted, “One of us is dead.” He added, “Don’t mess with novelists.”