Another feature of wealthy nineteenth century areas was club life. It was de rigueur for men to join at least one as a home away from home. Most are now gone. The only one surviving in the Heights, the Heights Casino, still functions because it is a sports club.

The first was the Long Island Club, later the Brooklyn Club, founded in 1865, which was originally housed in a mansion on Remsen Street later demolished for the Hamilton Club. Its proudest possession was an original Francis Guy painting of the Brooklyn Ferry area from around 1810, which was donated to the Brooklyn Museum when the club terminated.

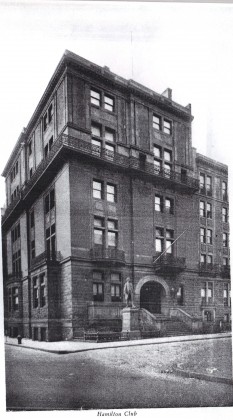

The Hamilton Club, an offshoot of the Apprentices’ Library and Lyceum, began as the Hamilton Literary Society and in 1830 became the Hamilton Library Association, expressing its interest in debating and its possession of a library. It was renamed the Hamilton Club in 1882 and built a clubhouse at the northwest corner of Clinton and Remsen Streets in 1884, using the former Long Island/Brooklyn Club mansion as a base.

In 1892 it added a statue of its namesake to the front yard (Figure ), which was removed to Hamilton Grange in Harlem when the club terminated in 1936 and merged with the Century Club. The building was demolished and replaced by an apartment house.

The club moved to Pierrepont and Clinton Streets (Figure 131), on which the back of the Brooklyn Trust Company was later raised. It then moved to 131 Remsen Street, which had been the home of James H. Post, president of the National Sugar Refining Company. It passed out of existence in 2002 and its home became a synagogue.

It was perhaps the glitziest club in the neighborhood, and the Brooklyn equivalent of Fraunces Tavern, which is owned by the Sons of the Revolution, a descendants’ organization. Since Alexander Hamilton was the apostle of big business in America, the club may be viewed as promoting those ideas. The actor George Arliss visited to see its portrait of Martha Washington.

It was perhaps the glitziest club in the neighborhood, and the Brooklyn equivalent of Fraunces Tavern, which is owned by the Sons of the Revolution, a descendants’ organization. Since Alexander Hamilton was the apostle of big business in America, the club may be viewed as promoting those ideas. The actor George Arliss visited to see its portrait of Martha Washington.

Admiral Robert E. Peary, the first to reach the North Pole, came there and was an associated club member. Several dinners were given for him, including one on January 5, 1907, at which he gave an account of his Arctic journey. Woodrow Wilson was tendered a reception while president of Princeton University (before he was President of the U.S.). Future president Herbert Hoover was a visitor in 1920, and Columbia University President Nicholas Murray Butler made a speech there in 1913. William J. Burns, who went on from Union military security service to found his own security firm, was also honored, as was NYC mayor George B. McClellan, son of the Civil War general, who served as mayor from 1904-1905.

The club’s major event was the Washington and Hamilton Birthday celebrations. The club was royally done up for the Hamilton observances. The grill was decorated as a forest, on one occasion with birch bark covering the walls. Menus were printed on wood, with animal skins and heads and stuffed birds.

The club featured souvenirs of Hamilton, including a lock of his hair, and two letters he wrote. There was also a copy of the ballad “The Drum” sung by Hamilton with Aaron Burr in attendance at the dinner on July 8, 1804, of the Society of the Cincinnati (a group of officers who had known Washington during the Revolution), of which Hamilton was president, a week before their fatal duel. Surprisingly, Hamilton and Burr had been friends and were witnessed leaving the old County Courthouse in Flatbush together arm-in-arm.

Starting in 1830, members often adjourned to Johnny Joe’s, an oyster bar on Prospect Street at Fulton Ferry, where they also held their reunions. The owner, John Josephs, was born a slave in Martinique around 1800, but as a boy was taken to New York by his master and freed. He worked as a waiter in private homes and then as an army servant under General Winfield Scott during the War of 1812. Scott would later become the hero of the Mexican War. In 1825 he married Louisa Britton, a former American slave, who became the cook in his restaurant.

At club gatherings at Johnny’s, members would sing an official anthem whose lyrics were:

Our trysting place at Johnny Joe’s

Our glorious John Joe’s

Where we all ate the oyster fries,

Down there at Johnny Joe’s.

When Josephs died in 1880 the Eagle obituary stated, referring to Henry Murphy, “This vestibule of the great structure should properly be christened as Johnny Joe’s monument, for who of all mortals more enjoyed his wine and oysters (and was more royally treated by him) that the immediate President of the Bridge Company, who is a distinguished Hamiltonian and whose portrait hangs in his ancient hall.”

The club had three vases given by the French government as thanks for courtesies extended their representatives during the ceremonies for the opening of the Statue of Liberty in 1886 when its sculptor, Auguste Bartholdi, visited the club.

Robert Furman is working on a history of Brooklyn Heights called “Brooklyn Heights: The Rise, Fall and Rise of America’s First Suburb,” to be published later this year.