Philip Livingston was a Manhattan lawyer, businessman and slave trader and his house on the Heights was his “farm” or country house from 1765 until his exile and death. He had purchased the land in 1750 from the Remsens. Livingston headed the “Low Church Party” in America and his Manhattan mansion was a patriot headquarters. Our information about the house is derived from Gabriel Furman’s (Furman Avenue)(no relation) Antiquities of Long Island (Monuments and Funeral Customs) published in 1875. He lived in the area and as the son of William Furman, one of the Village of Brooklyn’s founders and leaders, had been in it. He described it as follows:

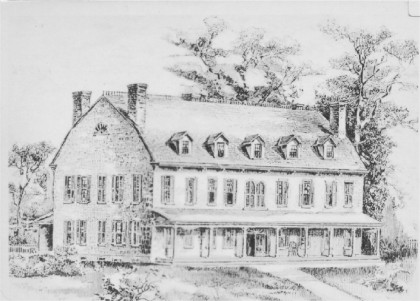

Another noted house in Brooklyn was the mansion-house of Philip I. Livingston, afterwards a member of the Continental Congress. This was a large frame building, actually forming two dwellings. The larger part, which was about forty feet square, Mr. Livingston erected for his son [Walter], who was a young man then travelling in Europe; who, upon his return, was to be married to a lady to whom he was engaged before he left home, and occupy that new house; but he was taken sick, and died abroad only a few months before his return home was expected.

This mansion, both the old and the new part, was finished throughout in the best and most costly style of that period, having much beautiful carved woodwork and ornamented ceilings, also Italian marble chimney-pieces sculptured in Italy. Most beautiful specimens they were; we have often admired them. This house, upon the death of its last owner and occupier, Judge (Teunis) Joralemon, in 1842, was about to be taken down, and these marble chimney-pieces were packed up for removal, when it took fire, and they, with the house, were destroyed. The gardens attached to the mansion, when the British took possession of it and converted it into a naval hospital in 1776, are said to have been among the most beautiful in America.

Livingston also owned a distillery on the shoreline at the River Road, later Joralemon Street, which is shown on the Ratzer Map of 1767. It probably made gin, originally the Dutch genever. Ships from the West Indies unloaded sugar cane here, which was crushed by wind and tidal mills. Local forests provided fuel for distillation. As the King’s Brewery during the occupation, it produced beer for British soldiers, of which they consumed twenty barrels a day. A ship known as a “bethel” was moored nearby and served as a place of worship for sailors from these ships and helped bring the Anglican Church to Brooklyn.

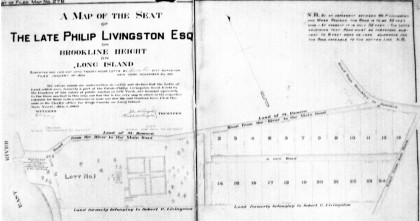

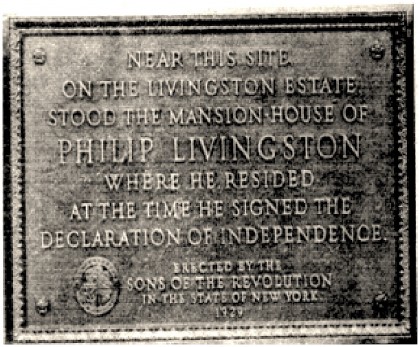

During the occupation, Livingston was forced to move to Kingston, which served as the patriot state capital, where he died in 1778, two years later. His Brooklyn house was used by the British as a hospital principally for soldiers with scurvy. Bodies interred on the property were regularly unearthed during development. William Furman (Furman Street) reported seeing some whose teeth were removed for reuse. This hard use ran the house and garden down. A site plan filed for the sale of the property freezes the exact moment in 1803 when country began to become city. Garden Place is located where the garden+ was and is named for the Livingston/Joralemon retreat.

The Livingstons were “patroons”, huge colonial landowners, and became prominent in military and public life since they owned the huge upstate property known as Livingston Manor in Dutchess and Columbia Counties, but also because they were among the few college-educated men in America. (The patroonships were abolished by New York State during the Jacksonian Revolution of the 1830s.) A cousin of Philip, Robert G. Livingston, owned the adjacent plot of land and house south of what would become State Street. Cousins included Robert R. Livingston who became Chancellor of New York State and as Ambassador to France negotiated the Louisiana Purchase for President Thomas Jefferson. Philip’s brother William served as governor of New Jersey (and has a town there named for him), and William’s son Henry Brockholst (who was a trustee of Philip’s estate) became a justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Part of the family moved to Louisiana, where they continue to be prominent. For the nation’s centennial, the house was painted as a “historic recapture” (i.e., it is not from life) by James Ryder Van Brunt, descendent of Dutch Brooklynites from Henry Pierrepont’s sketch from memory.

Robert Furman is working on a history of Brooklyn Heights called “Brooklyn Heights: The Rise, Fall and Rise of America’s First Suburb,” to be published later this year.